Biography of Marc Chagall

Biography of Marc Chagall

1903-1914

Starting out in Russia and discovering Paris

Marc Chagall was born in Vitebsk (Belarus, which was still an integral part of the Russian Empire) on 7th July 1887.

He was the eldest of nine children in a poor Jewish family – his father was a herring merchant.

Despite the art world being a far cry from his humble background, he was introduced to painting while going along to the studio of a local painter – Jehuda Pen - after his secondary schooling was cut short. Not long after that he met Bella, the daughter of modest jewellers, who became his fiancée and source of inspiration.

From 1907 to 1909, he moved to Saint-Petersburg, where he enrolled in several academies before working in the studio of Léon Bakst, a set designer for the Ballets Russes. It was here that he came across the works of the Parisian Avant-Garde and began dreaming of going to Paris.

His dream finally came true in 1911 thanks to a grant from the lawyer Vinaver. This was the beginning of his first trip to Paris and his art took a radical new direction as he adopted the Avant-Garde’s discoveries – from Fauvism to Cubism – for his own, brightening his colours in the process.

Chagall moved to the artist’s residence, La Ruche, in Montparnasse where he met fellow residents from the Paris School, artists: the Delaunays, Léger, Soutine, Lipchitz, Kissling, Archipenko, Modigliani; and writers: Max Jacob, André Salmon, Blaise Cendrars and Guillaume Apollinaire.

In 1912 and 1913, he exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants and produced his first masterpieces (including Golgotha, 1912, MoMA, New York and Homage to Apollinaire, 1912-1913, Eindhoven).

His first private exhibition took place in 1914 in Berlin, organised by Herwarth Walden in the Der Sturm Gallery. From Berlin, he returned to Vitebsk where the war forced him to stay put.

1914–1922

The “Russian years”

In 1915, Chagall married Bella in Vitebsk, who gave birth to their daughter Ida in 1916.

The artist exhibited in Moscow and Saint-Petersburg and socialised with intellectuals and Avant-Garde artists.

In 1917, he supported the ideals of the Revolution: the Jews of the Russian Empire were at long last granted citizenship and, upon being appointed director of a Fine Arts School as well as Vitebsk Commissioner of Fine Arts, he believed he could change mentalities through artistic practices. But his contribution by the first anniversary of the Revolution was misinterpreted by the new authorities and teachers he brought from Saint-Petersburg and Moscow to his school, and Malevitch, Lissitzky, Pougny and others – all Suprematists – took a stand against him, forcing him out.

1920 therefore saw him moving to Moscow where he worked on the decoration of the Jewish theatre, now acknowledged to be the masterpiece of his youth. Despite his material struggles, this was an intensely prolific period for the artist: in his paintings (Promenade, 1917-18, State Russian Museum, Saint-Peterburg – Over the Town, 1914-18, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow - Apparition, private collection, Saint-Petersburg) with confident lines and strong, pale colours, he developed a personal vision blending fantasy and the fantastic with borrowings from Futurism, Cubism and Suprematism.

In 1922, he left Russia for Berlin, where he was recognised thanks to Walden’s work. It was here that he produced his first engravings, for Ma vie, his poetic autobiography.

1923-1939

The interwar period, in Paris

In 1923, Chagall returned to Paris with his family and began to work for the great art dealer Vollard, who commissioned illustrated engravings from him for Gogol’s Dead Souls and then La Fontaine’s Fables.

He travelled around France with his family, depicting its landscapes in drawings and a wide array of delightful gouache paintings.

By the 1930s, his artistic influence began to hark more from Impressionism and the ambient return to Classicism.

In 1931, he was invited to Palestine by the Mayor of Tel Aviv with a view to founding a Jewish Art Museum. On his return, he created 40 gouache paintings to illustrate the Bible in engravings, once again for Vollard. These are now on display at the Musée National Marc Chagall in France. He also travelled around Europe.

In 1935, after a trip to Poland where he got the full measure of anti-Semite sentiment, he was branded a “degenerate artist” by the Nazis.

In 1937, he at last became a French national with the support of Jean Paulhan.

He was a frequent visitor to the Maritain Salon and rubbed shoulders with the writers Breton, Delteil, Soupault, Cocteau, Reverdy and Arland whose work he illustrated.

When war broke out, he took refuge in Gordes, in the free zone, but was ultimately left with no choice but to leave Occupied France in 1941.

His daughter Ida managed, against the odds, to forward all of the works from his studio to New York where he made his home.

1941-1947

The war and exile in the USA

In New York, Chagall got back in touch with many friends, writers and artists who were also refugees: Léger, Masson, Mondrian, Bernanos, Maritain and Breton. He exhibited at the Pierre Matisse Gallery.

He renewed old ties with Russian writers that had been sent to New York by the Soviet ally. Talking Yiddish once again with them and discovering the vast American snowscapes, which reminded him of the landscapes where he grew up, rekindled Chagall’s inspiration in Russia – even though his paintings were marked by the war and anguish for the fate of Jews. Christ, who symbolised the martyrdom of Europe’s Jewish populations, became the central figure in his paintings for a while (White Crucifixion, 1939, Chicago Art Institute - Obsession, 1943, National Museum of Modern Art, Centre Georges Pompidou).

In 1942, he helped to create the ballet Aleko in Mexico (music by Tchaikovsky), for which he produced the scenery and costumes.

In 1944, just as peace was dawning, Bella died suddenly. For all that, Chagall created the decoration and costumes for Firebird (music by Stravinsky) a year later and soon after met his new partner Virginia Haggard.

By the end of the war, Chagall had gained worldwide recognition: he attended the retrospectives of his work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and then in Paris and elsewhere in Europe.

1948-1985

His return to France

In 1948, Chagall returned to Paris before buying a house in Vence in 1950.

Since his partner Virginia Haggard had left him, in 1952 he married Valentina Brodsky, who was also a Russian Jew.

In the South of France, he began to branch out technically and worked with ceramics at the Ramiés in the Madoura Gallery in Vallauris, in the same studio as Picasso.

Through his friendship with Father Couturier, he became involved in the programme of Notre-Dame de toute Grâce Church in Assy where he created a large ceramic mural and his first stained-glass windows for the baptistry.

1955 saw the beginning of the project to decorate the Chapels du Calvaire in Vence, which then became known as the Biblical Message cycle.

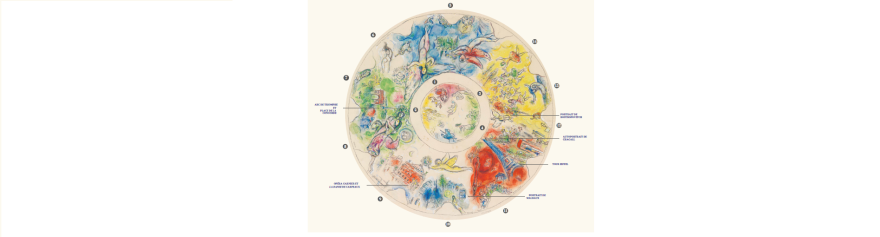

Over 20 years, the artist fulfilled countless important public and private commissions: stained-glass windows (for example in Metz, Reims, Jerusalem, the UN HQ in New York, Zurich and Mayence), paintings (ceiling of the Opéra National de Paris, painted murals in the New York Metropolitan Opera), mosaics (e.g. The Four Seasons, 1974, Chicago) tapestries (for example the Gobelins tapestries he wove for the Knesset – Israeli Parliament) and stage work (set design and costumes for Daphnis et Chloé at the Opéra National de Paris).

At the same time he produced a great many lithographs and engravings for illustrations, particularly for Tériade or his Paris-based trader Aimé Maeght.

In 1966, he donated the Biblical Message to the French State, which was firstly exhibited at the Louvre before inspiring the creation of the museum in Nice – inaugurated in 1973 in Chagall’s presence.

He continued to work right up until his death on 28th March 1985 in Saint-Paul-de-Vence where he is buried.

associated.content.title

In the footsteps of Chagall - Route through the city

In partnership with the city of Nice

Chagall. A Cry of Freedom

Dispositivo Esplicativo per il Soffitto dell'Opera di Parigi

Il tributo di Chagall alla musica e a Parigi